Joe Dunthorne’s new – and first non-fiction – book, Children of Radium, is out now.

Peter did not take the one empty seat on the free transfer bus to Frankfurt Airport. For this reason, he never struck up a conversation with a young Canadian woman gripping a tasteful leather holdall in her lap. And she never had the chance to admit to him that the bag was massively impractical and awkward to carry and caused her persistent lower back pain that she endured for reasons of vanity alone. And since they never got chatting, they never fell in love or married and Peter never applied for citizenship after relocating to Vancouver. In turn, he never went through the brutal break-up, dumped for an artist whose heartwarming street murals on libraries and social housing were so prominent throughout the city that Peter stopped being able to leave his third-floor apartment or even look out from his balcony. He never reached the point where he had pasted kitchen foil over the living-room windows so that he could lie on the floor in the dark, his laptop the only source of light as he obliterated his own self-worth by tracking the value of the artist’s limited-edition prints on streetartcollector.com.

No. He stayed standing on the bus, watching the planes rise from the earth. Beside him was a young woman with short bleached hair whose phone had died, taking with it her boarding pass, and who was swearing quietly but consistently while moving her weight from foot to foot. She was late for her flight and knew that she did not havethe time to buy a charger or queue at the desk to get a printout. So while the bus made the short journey down the autobahn, Peter lent the woman his own phone and watched as she, with great intensity, downloaded the Lufthansa app, swore again – loudly this time, a single, well-enunciated fuckit – as she realised that she could not remember her login details, then reset her password, navigated to her emails in order to click a security link and only then started downloading her boarding pass to Peter’s phone. The process was still unfinished as they jogged together through the terminal, the young woman holding Peter’s phone aloft for a better signal while his suitcase’s wheels made an unseemly panting noise. Huh-uh-huh-uh.

Peter was someone who liked to arrive at an airport hours in advance of his flight, just on the off-chance that he might be waylaid by something unexpected like, for instance, falling in love with a charismatic stranger. They jogged down white tunnels together, Peter privately enjoying the vicarious sense of jeopardy. It was almost a disappointment that, when they reached gate A34, the plane was delayed and had not started boarding. The woman had time to plug in her phone at a charging station. Peter stayed with her, happy to receive a steady stream of gratitude. I can’t tell you how much this means. You saved me. Thank you. They both watched the phone shudder into life. It made a high ding sound, as though to indicate a good idea. That’s when she, Leanne, wrote her name and number in his phone. They exchanged a hundred messages before their planes took off.

As a result of this, Leanne never got back with her tricky on-off girlfriend, never endured years of IVF, never single-parented a difficult, opinionated daughter who, between the ages of three and seven, insisted that everyone walk through every door in height order, shortest first. Leanne never had to witness one particular occasion when breaking this rule provoked a tantrum so severe that her child bashed the back of her own head against the café’s tiled floor, resulting in a minor skull fracture. No. Over the next fortnight, Peter and Leanne made plans to spend a weekend together in Berlin. They could not decide between two equally nice and equally cheap Airbnbs – so Peter tossed a coin.

They walked together through the city, talking all the way out to the Wannsee, where they swam in their underwear in the silver water. They were shivering by the time they got back to the apartment, and so decided to try and work the ridiculous-looking antique central heating system, with its beautiful tiles depicting exotic birds on the stove surround. They descended together to the shed in the communal front garden, finding it impossibly romantic and fun to watch each other shovel black gold into scuttles and drag them upstairs, their hands sweaty and coal-dusted as they gripped the – it was pleasant to even say the word – scuttles. It briefly struck Peter that they were fetishising an industrial past they had no real relationship to, but neither of them judged the other for it. All weekend in the large warm room they had sex that got better with each iteration.

Smoke rose from the roof of the apartment block they did not stay in. They were not among the two dozen residents evacuated, some already in their pyjamas, descending five floors down the concrete stairwell while the alarm blared. They did not stand outside, staring up at the billowing black cloud as it blended with the night. They did not reassure themselves that it was probably nothing serious and decide to go out in the clothes they were wearing, first to some local bars and then on to Griessmuehle, channelling their adrenaline into a suddenly serious commitment to techno, and so never experienced the pleasure of that extraordinary night – among the best of their lives. They never came back to the apartment block thirty hours later to find the lift still not working and a police car outside. They never climbed the stairs slowly, calf muscles burning. They did not smell the chemical stench of burnt insulating foam, how it lingered at the back of their throats. They never lay in bed listening to a man sobbing through the wall. They did not remain side by side, completely still beneath the sheets, unable to sleep or touch each other as they waited and waited for the sound to stop. They did not eventually give up and put in ear-plugs, only to discover that the noise lived on inside their heads, that it followed them through the rest of weekend and only ceased when they agreed to never see each other again.

No, shortly after returning from Berlin they moved to a little basement flat on the Kent coast because Peter got a job at the university and Leanne could work from home. They couldn’t see the sea, which was why they could afford the flat, but they could hear it, scraping its fingernails down the shale. They bought matching neoprene booties and, every weekend, swam in the green ocean under the gaze of the offshore wind farms.

They started trying for a baby. Leanne was forty and Peter’s sperm count was low, but not disastrously, so they discussed whether to keep going on their own, switch to IVF, or consider a sperm donor. They went for the latter, narrowing down their choices to a handsome young kayaker with a lightly bearded face and a kind-looking Scottish carpenter with outrageous hair. The kayaker won and Leanne gave birth at home, in a pool that filled the entirety of their living room. They had long ago decided on the names: Natasha for a girl and Callum for a boy, and they had a Natasha. She was not a sleeper and so Peter bought a white-noise machine and put it on, loud, right next to her cot. Of all the available sounds, the only one that even vaguely soothed her was called ‘deep-sea rollers’. They kept it on, day and night, drowning out the sound of the actual ocean. Sometimes, when he was deliriously tired and bouncing his red-faced daughter in his arms, Peter felt he could hear them, all the millions of other possible Natashas and Callums, cascading away in all directions, sleeping and not sleeping, screaming and not screaming, being easy and not easy to love.

Even though neither Peter nor Leanne had the slightest interest in sport, Natasha grew up to be preternaturally good at tennis. When she was ten they paid for her to have twice-weekly private tuition on the courts by the recreation ground, which they could afford because Leanne’s mother did not live to ninety-nine and so require expensive round-the-clock care, but instead died at eighty-five with an unmortgaged house and a clean will.

When a summer storm brought half the beach into their front room, destroying everything, they did not spend two months living in an Ibis, battling for an insurance payout that never came, but instead moved straight to a place further inland along the coast. They grew aubergines in their back garden, big ones so shiny they could see their reflections in them. Mosquitoes had become an all-year-round problem so they slept under a huge net, which gave them a somewhat royal feeling they quite enjoyed. Peter had a number of spongy, malignant mounds scooped out of his arms and legs. Natasha gave up tennis for ethical reasons and, after making it clear that she would probably never come back to Europe, sailed to Santiago to work for an NGO. She got married to a Chilean man called Agustin and they had no ceremony. They decided not to have children, which Peter and Leanne totally understood and even admired.

The four of them stayed in contact over video calls. They often left the camera running all day long, their laptops open on their kitchen tables, thousands of miles apart, so it could almost feel like they were housemates, enjoying the mundane and intimate noises of each other – loading the dishwasher or blowing their nose.

Peter and Leanne were not at home on the day the intruder broke in. Leanne was not napping on the sofa and Peter was not in the garage office playing solitaire. Thus, Peter did not experience a profound moment of self-knowledge as he was forced to face the realities of his own cowardice. No, instead they were walking on the beach when they got a phone call from their daughter telling them not to return to the house. Natasha was surveilling their kitchen via video call and there was a young man with a wheel brace opening their drawers and cupboards. She watched the intruder eat cold clam chowder from a tin, breathing heavily as he scooped up the thick liquid with his hand. He was a boy really, a child, Natasha said, his bare scalp peeling, so she made them promise that they would forgo the authorities and let him leave on his own terms. They said they would but then hung up and called the police. They debated whether to tell Natasha this and, in the end, thought it better not to, forgetting that she was still watching from her laptop as the boy was pursued and brought to silence.

Every Sunday, Peter and Leanne cleaned the beach with litter-grabbers, filling a bin bag. One day they found three full backpacks washed up at the tideline. Another day they found a porpoise, still breathing. Peter’s cancer did not return and he did not have to choose whether to go through chemo again. Instead, he was diagnosed with a rare, aggressive dementia and, in close collaboration with Leanne, he began making very specific plans for his own death.

Shortly after his eighty-sixth birthday, he drank Lagavulin 24 Year and looked out at their garden. Through a connection at the local church, Leanne had managed to arrange a delivery of medicinal-grade opiates, a tiny syringe and a machine for automated self-administration. She knew that she might be jailed for helping him but she was prepared for all eventualities. It was February and their big acer had only now turned a magnificent red colour, like it was sucking blood out of the earth. He and Leanne held hands. Natasha and Agustin watched, muted, from the laptop screen. In truth, Natasha was struggling to even look at her father, and instead she mostly watched her own image in the bottom-right-hand corner. She worked on her expression until it seemed like the right one.

Peter rested the pad of his thumb on the textured blue button. Leanne reminded him that he was still free to change his mind, that she would stay with him no matter what. But he did not decide to live and she was not obliged to care for him while he rapidly lost the power of speech, became violent and ultimately required three orderlies to sedate him and take him away to where he would die slowly, confused and betrayed in a pretty room by the sea.

He pressed the button and the machine said shush.

A sweet small bird landed on the feeding tray. He looked at it and then he closed his eyes. He wanted that to be the last thing he saw.

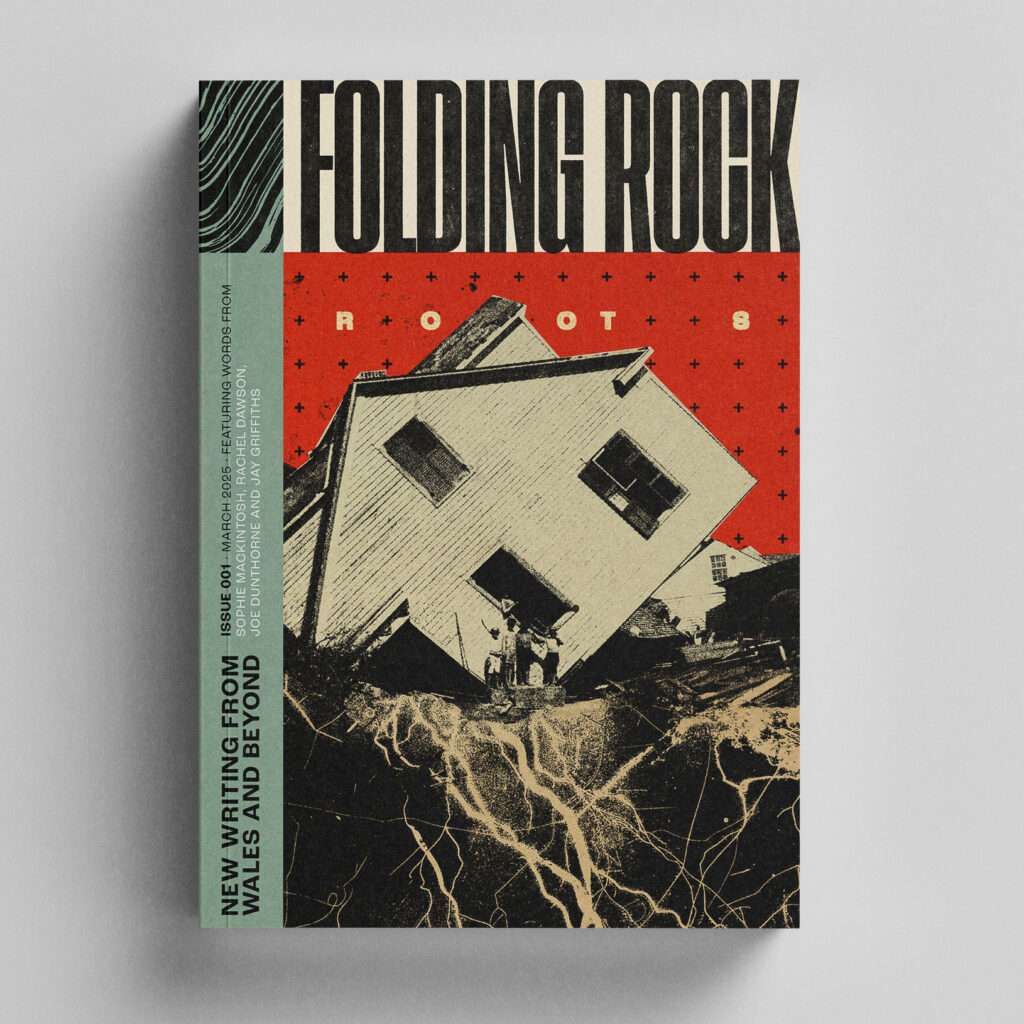

Featuring new work from writers including Sophie Mackintosh, Jay Griffiths, Joe Dunthorne and Rachel Dawson.

Roots can take hold in myriad ways: in the places we are born, the ones we come from, and those we learn to call home. They bind us to our histories, our environment, and the people who surround us. Our roots embroider the bedrock of everything we do – for better or worse. They are the vessels that feed our future.

Joe Dunthorne is the author of three novels and a collection of poems. His debut novel, Submarine, was translated into fifteen languages and made into an award-winning film. His latest book, Children of Radium – a memoir about family and chemical weapons – will be published in April 2025.