Last October, every two or three days, I would wake up in the middle of the night and make Sylvia Plath’s lemon meringue pie. I made so many pies that month – and I can blame them all on Taylor Swift.

I would set an alarm on my phone so that I could join one of the grainy TikTok livestreams of The Eras Tour as it made its way around North America; watching, baking, and all the while perfecting Plath’s recipe, which I’d found in The Paris Review.

I’d wake up at 1 am to a blissfully silent house, put the kettle on for a cup of tea or coffee, grab some biscuits and watch the opening eras (Swift took us on a journey across all of her eleven albums throughout each night) of the show from my sofa. By the time we reached Red, the third part of the night, I’d get up and move into the kitchen.

I’d begin by rolling out the short crust pastry – already pre-made and kept in the fridge for a few hours. I’d stick it to the walls of the pie dish, line it with parchment paper and fill it up – with uncooked rice at first, before eventually graduating to ceramic baking beans. My craft was constantly improving.

Initially, I would spend hours whipping the egg whites for the meringue by hand, pausing only for the surprise songs segment of the concert, often crying, always sweating and cursing, and inevitably returning to it the next time.

A few weeks in, my friend Helen, who was usually up with me from her house in County Tyrone, ordered me an electric mixer that improved not only my quality of life and the standards of the bake, but also my belief in the goodness of people that had perhaps faded away slightly since the summer of dreams had ended.

During Midnights, the closing era of the show, I’d wash the dishes, the golden lemon curd glistening on the bottom of the pan. I’d finish the cold dregs of my tea and then take the pie out of the oven before heading off for another hour or two of sleep.

I’d have my first slice for breakfast after the school run, my brain still hazy, the sugar and the acidity waking me up and easing the confusion of a self-imposed feeling of jet-lag.

Swift left Europe in late August and was, by October, back in the States, leaving the European fans, such as me, bereft and yearning for more. We had all felt a new lease of life during her record-breaking and generations-bonding presence here throughout the summer. When I say here, I mean that she was always in proximity to our time zone, and if one had enough resources and determination, they could get to the next tour stop within hours.

Even just being in the same city Taylor Swift was playing seemed good for the soul. Swifties are known for their kindness, infectious joy, immaculate fashion and economy-boosting glittery presence. It was a summer of girlhood that affected people of all ages and genders, and even the non-fans couldn’t deny its cultural impact.

And then it was gone, leaving in its wake a trail of friendship-bracelet beads and hazy memories. It has been reported that fans attending The Eras Tour experienced post-concert amnesia, when they couldn’t recall the details of the night – and by now Taylor Swift herself has confirmed that she wanted the show to be full of so many different experiences in terms of visuals, dance styles, choreography and costume changes that the brains of the onlookers would be overstimulated and unable to create detailed photographic memories, focusing instead on creating a general core memory of the experience.

One way of combating this, for me, a lover of details, was to watch as many live shows as I could. Dubbed ‘shitty livestreams’ for their intermittent and laggy quality, they were lifesavers to the millions of fans who weren’t lucky enough to secure tickets, and to the ones, like me, always wanting more.

Yes, obsession is a persisting trait of the fandom. Any fandom.

There’s an image that comes to mind when I think about the term ‘fangirls’, that I believe comes to mind for most people. A screaming, frantic, red-eyed teenager, mouth agape and pulling hair out of her head.

I’m a little angry with myself for conjuring such a basic and condescending picture, knowing that fangirls can and do look and behave in all sorts of ways – and aren’t just teenagers. I’m an example of that, of course: a woman approaching her late thirties, a mother of two, attempting to forge a literary career for herself. There are millions of us and we’re not a caricature; we are simply at times so overcome with joy it may appear childish to the onlooker. It’s not, and excitement shouldn’t be assigned to just one group of people – in fact, more should try it. It hurts nobody.

We’re not all girls, either, but the criticism of fandoms is often clouded by misogyny and homophobia.

It has been suggested that the first artist to have widespread ‘fangirls’ committed to his art and life wasn’t a musician, but a poet. Lord Byron was followed by crowds of his admirers, both male and female, who would consume every new snippet of his poetry as well as send him a never-ending stream of love letters. Franz Liszt became the first composer with a fandom. And of course, once in the twentieth century, there were more obvious names like Frank Sinatra, Elvis Presley, and The Beatles, who had to pause touring because of the wild behaviour of their fans.

I’ve had a fangirl tendency from the very beginning.

Music was always around me as a child. My mum loved classical music – and anything from the seventies. My father would spend evenings watching tours of his favourite rock and heavy metal bands on VHS tapes, and it felt like a sacred time for him, when he’d reconnect with his youth, the memories of the golden olden days. I wonder if in ten–twenty years it will be me, hunched over The Eras Tour film on my laptop.

Ultimately, it doesn’t matter what kind of music you obsess over if it moves you, if it connects you to the deepest parts of yourself. To suggest ‘fangirls’ exist only in pop culture is a dishonour to so many people’s experiences.

I have two older brothers. One of them liked hip-hop, and the other one’s nickname is Metal, even now. I remember learning about the death of Kurt Cobain, possibly the first time I came across the term suicide; afterwards I couldn’t sleep at night and imagined his head and a gun and lots of blood. I remember learning about the murder of 2Pac and crying, I think mostly because of how visibly shaken my brother was by the news.

My first obsession of choice was The Kelly Family, an Irish band that was huge in Poland and Germany in the nineties. I remember begging my mum to let me wear her flowing, flowery maxi dresses because this is what the Kelly sisters wore. Then came the Hanson brothers, and I would spend hours recording imaginary interviews with them on my multicoloured plastic boombox. I played the roles of both the radio presenters and the brothers themselves, and the recording would go on until the tape ran out.

Then of course it was time for Spice Girls and Backstreet Boys. One day my childhood best friend came to hang out and, because she was the dominating half of the friendship, she decided to give me a lesson in style by pointing, one by one, at all of the girls and asking me what was wrong with their outfits. This felt like a test that I was destined to fail; they all looked perfect to me. Another friend, who was from a family economically better off than mine, had gotten tickets for Backstreet Boys playing in Poznań during one of their tours. I remember watching videos from the tour and seething with jealousy.

I joined their official fan club instead. Photographs of Brian and Kevin against an orange backdrop are still at the back of my childhood photo album.

Little did I know then, my time would come.

I don’t actually remember how I got into Taylor Swift. It feels like she was always around. I wasn’t obsessing at first, but I was aware of her movements, and there are songs in her multi-genre-spanning discography that accompanied important landmarks in my life.

I danced to ‘You Belong with Me’ at nights out during my first year of uni. After publishing something on a Polish news site and receiving vile comments, I listened to ‘Mean’ on repeat. I cycled alongside Cardiff’s Taff Trail with 1989 in my ears and felt, for a moment, free and happy, during a time when I was stuck in a toxic relationship.

Reputation came out on the day of my twenty-ninth birthday and I was first in the line at HMV to pick up my pre-order. I missed out on the Lover era as I was too busy with two young children to consume anything new, but by lockdown albums I was back. folklore and evermore moved me with a lyricism that I somehow missed from the previous albums, despite it being there from day one.

And on the 20th of October 2022, I did something that would firmly alter the rest of my life: I pre-ordered a cassette tape of Midnights, Swift’s tenth studio album that was due to be released the next day. This pre-order allowed me, months later, to purchase my first tickets to The Eras Tour in the fan pre-sale.

The Eras Tour summer was like church. The closest proximity to feeling the union of other people, the sing-alongs towards something seemingly greater than ourselves; ripping our throats to shreds, the communal energy release.

Once upon a time it was football games.

I used to go to the home Lech Poznań game, back in Poland, every fortnight. We would stand in kocioł, the cauldron, a part of the stadium reserved for the true fanatics – cult-like ultras with a clear hierarchy of rules and respect. No sitting was allowed except for the half-time break, no food was to be consumed, no photographs of the game taken – forget about selfies. After each game, my throat would be on fire and my ears would ring till the next morning, but it felt good, like I was a part of something important, bigger than myself.

But something shifted in me one day. A person of colour had purchased a ticket to this section of the stadium by accident – nothing on the team’s website suggested it was reserved only for the whitest and mostly male supporters – and was removed forcibly by some of the gang. I only went to one more game after that, and my heart wasn’t in it. You were always observed, and if you didn’t sing loud enough or jump high enough with the rest of the ultras you too could be moved. Until that day it had felt like the right thing to do, and I took pride in being one of the only girls allowed to be there.

After the incident I felt relieved that I was moving to a different country soon and would naturally stop attending the games without the need to explain myself. The only memory of my time with the hooligans that remains is a tattoo of the football team logo, in blue ink, that I had done on the day of my eighteenth birthday in secret. I think of covering it up daily – but in the meantime, it serves as a reminder to remain humble.

Every time I look at it I think of how much criticism the fandom of Taylor Swift gets because the base of it is girly, glittery and glorious, whilst the polar opposite, the bare-chested, alcohol-fuelled toxic masculinity often representing football fans, gets a free pass. It all circles back to misogyny. There is a huge number of people who despise seeing young women enjoying their lives to the fullest. To be a fangirl, then, is actually a rebellious act.

My girlhood was stolen from me by men who had no reason to be in my life so early and then, as I grew older, by some of my own decisions. Becoming a fangirl helped me reclaim myself. I am no longer committed to seeking male validation; my life has become filled with the pursuit of things that bring me genuine joy.

The adrenaline high after securing Eras Tour tickets lasted a long time. Everything felt possible after beating thousands of people in that queue.

I finished writing the manuscript for my first book the day before Taylor Swift’s concert in Cardiff. I recorded myself typing the final words, my nails already adorned in the colours of all of the eras, my wrists thick with friendship bracelets. When I left the coffee shop, I could hear the soundcheck from the stadium. Yes, I cried. In my sleep-deprived and emotionally fragile state, everything felt like I was in a film.

The next day was like a wedding day. I booked an early appointment with a hairdresser and I asked her to braid my hair and spray it with an entire can of antiperspirant (my head sweats so much when I’m dancing) and cover it up with another can, this time of hairspray, so the braided space buns remained intact for most of the night. She carefully adorned my head with the daisy clips I’d brought with me. When I paid, I left her the biggest tip yet, and she told me to take it easy for the rest of the day. She could probably sense the complete state of euphoria I was under, and when I left the building I was as close to floating as humanly possible.

I put my dress and make-up on in my friend Abbie’s hotel room (a fellow Swiftie who happened, also, to be my brilliant editor). I’d pinned a golden dragon brooch to my bag, a tribute to both Wales and ‘Long Live’, Taylor’s emotional song about the legacy of her music and fans. On the way to the stadium a little girl stopped me and told me I looked so pweety. I gave her a bracelet and a hug. The happiness and unity was palpable.

Each Eras Tour concert was a celebration. Of music, of safety to be oneself, of nearly twenty years of memories across generations, and of creativity. We all danced in unison, sang till we couldn’t anymore, and our eyes were wide open and glistening. Can you believe it? we seemed to ask each other wordlessly. Can you believe how much feeling one person can hold? Our veins pumped dopamine-filled blood throughout our bodies.

During ‘All Too Well’, a ten-minute song that Swift used as a closing track to the Red era on tour, a song that had stadium-fulls of people screaming fuck the patriarchy in unison (a direct opposite of what used to happen back in my hooligan era), a man wearing all black tapped me on the shoulder and handed me a guitar pick. Taylor’s team gave these, often used by Taylor in previous concerts, to fans throughout the tour as a way to connect to them and create an even more memorable experience.

When I looked down, my plectrum had a picture of Swift in her self-titled era, the time she released her debut album at sixteen. I immediately thought back to finishing my first manuscript the day before, and took it as a good omen.

I was about to enter my own debut era. This autumn, nineteen years almost exactly to the date of Taylor Swift’s first album release, my first book is finally arriving to meet the world.

I believe that, for some people – and I’m one of them – the object of our obsession acts like a mirror. For an unknown reason, at some point, I decided to obsess over Taylor Swift. I will never become a pop star myself – and have neither the desire nor talent to do so – but I can become a person with impeccable work ethics, who has a clear vision for her career, who isn’t afraid of feeling everything strongly and making art about it, who can commit to greatness, and interlope everything she writes with references that sometimes will take years to become clear.

Outside of music, the only other artist I could call myself a fangirl of is Sylvia Plath. And here I’m in good company, because Sylvia Plath herself had a strong fangirl inclination that became clear to me when I started to read more about her life. Plath was obsessed with Dylan Thomas and the idea of meeting him. She’d spend days waiting for him outside his usual New York hangs, and even attempted to bump into him in the corridor of his hotel. Later in her life, her obsession would turn to fellow women writers. She tried to strike up a friendship with Doris Lessing and Stevie Smith, sending a letter to the latter where she proclaimed herself a ‘desperate Smith-addict’ and inviting her ‘to tea and coffee’.

The connection between both Plath and Swift is very clear in my mind, as are the reasons why I have at some point unconsciously decided to become a great fan of both. The emotional intensity and confessional artistry, combined with the attention to language of both, is what I aspire to embody in my own work.

When The Eras Tour arrived at its final stop – Canada, mid-November 2024 – I arrived back in Poland.

My father’s health had been declining drastically and he was, by then, receiving end-of-life care. I flew in to ease my mum’s efforts in looking after him, and with the hopes I would have a chance to say goodbye.

It was a mentally and physically exhausting time, and I didn’t continue my tradition of waking up to watch the shows throughout the night. I caught up with the surprise song sets first thing in the morning instead, and some of them felt, the way they often did, pointed. The ‘You’re on Your Own, Kid’ x ‘Long Story Short’ mash-up felt especially fitting and I rewatched it often throughout that week.

‘Long Story Short’ is a closing song on the evermore album and personally, so far, the subject of my only tattoo based on Taylor’s music. evermore is the most healing from her discography for me; it takes the listener through the hardest times of crisis, heartbreak and disappointment to land at long story short, I survived. All of the hardship ends eventually. The tattoo I got the day I finished working on my manuscript, that hazy day before Taylor played in Cardiff, is of a book, with the song title on the cover and a tiny daffodil in place of a bookmark. Back in Poland that November, I was a kid again, alone in my childhood bedroom, facing one of the scariest times of my life, yet I held inside me the knowledge that I would be okay one day. Taylor’s songwriting helped me immensely.

I listened to evermore a lot that week. Running errands, cleaning, hanging out the washing, waiting for the nurse to arrive for her daily check-up on my dad.

Above his bed hung a photograph of a young Ozzy Osbourne and I spent some time looking through his photos – he always had a band shirt on, and apparently he got to travel to gigs quite a lot before my brothers and I were born – and handmade CDs bearing his familiar handwriting: Deep Purple, Queen, Metallica. I asked him multiple times if he wanted to listen to any of it, but in the end he chose silence and birdsong.

In my room, three freshly washed black T-shirts lay on top of each other. My Eras Tour shirt, Black Sabbath’s Never Say Die! and one with a painting of Jimi Hendrix on it. I arrived in the first one, and the last two were our choices for my father’s final outfit, and I nestled them all together until the decision was made.

The last evening of my dad’s life was slow. Snow was gently swirling down outside, settling on the communal gardens he spent so much of his life tending to. I played evermore again, quietly from my phone on the kitchen counter. I was beating up egg whites for meringue once more, eager to busy myself with something productive – something of service.

In the end, the pie ended up largely uneaten on the freezing-cold balcony. Dying is very much like the beginning of life: it eclipses everything else.

One year, my husband and I took my mum to see Patti Smith. She happened to be playing in the Welsh Millennium Centre in Cardiff during my mum’s visit from Poland and we managed to buy her a ticket. Because we didn’t buy it at the same time, we were sitting separately from each other, me and James towards the back, my mum closer to the stage. During ‘Gloria’, Patti came down to the audience and eventually got close to my mum and started singing to her, and they danced together for a moment. We saw that happen on the screen, and the happiness on my mother’s face made me want to weep. The connection between them was obvious, albeit brief, and I couldn’t help but think of all the things my mum went through, was going through, and how that brief encounter with one of her heroes offered her some kind of healing, some kind of hope – a type of joy that not many other things could have given her. I saw my mum as a young girl then, briefly, so excitable and in awe. She remained starstruck for some time afterwards.

In the end, the last thing my dad ever wore was that Jimi Hendrix T-shirt.

In the end, I feel like we’re all fangirls here.

Across the board, music genres and art disciplines, all we do is look for something to unite us, or to free us; to take us through the hard times. It’s not the idea of heaven that keeps me going, but the possibility of my favourite artist’s new tour and my favourite writer’s new book. It’s not the idea of grandeur that propels me to write, but the inability to pretend I was born to do anything else. I hope that when it’s my time to go, I’ll go wearing my worn-out Taylor Swift T-shirt, listening to my favourite songs and recalling the gold dust of memories accumulated over a lifetime. I want to leave with the taste of Sylvia’s pie still on my tongue, a life made sweeter than sour.

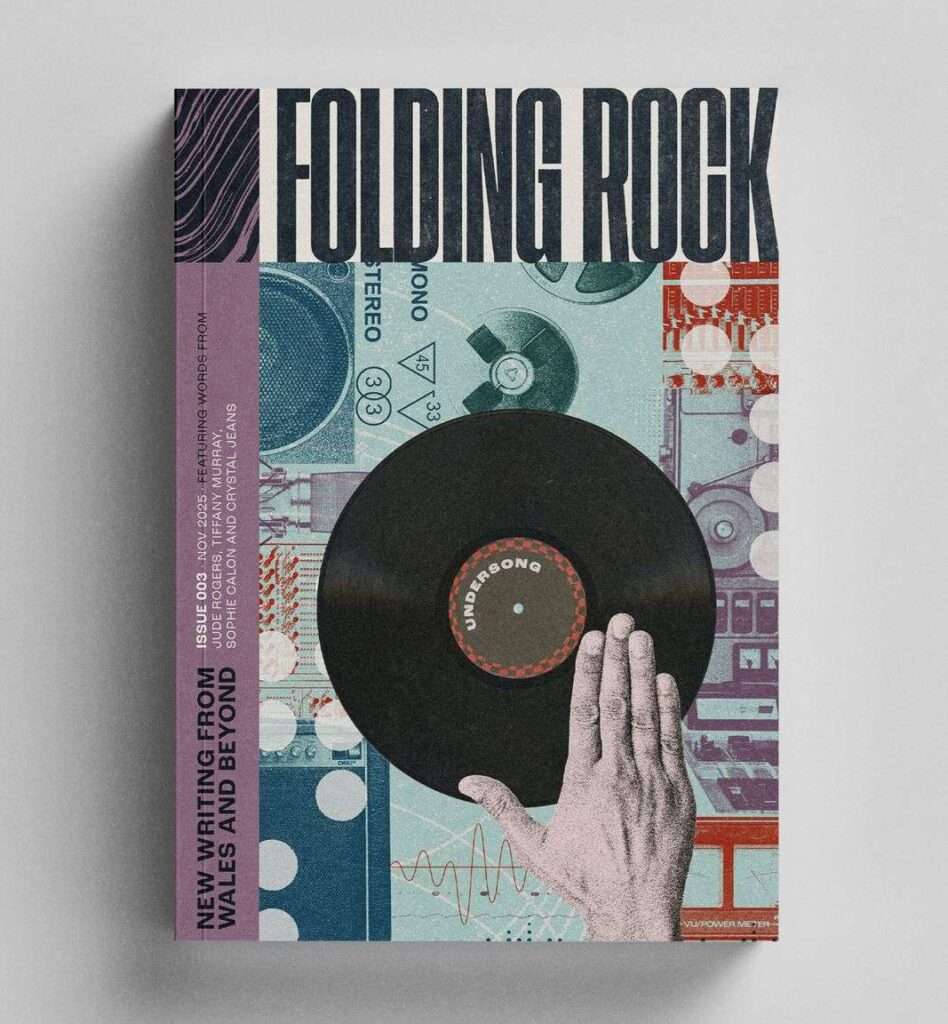

Issue 003: Undersong

Featuring new work from writers including Gosia Buzzanca Jude Rogers, Sophie Calon and Crystal Jeans.

Something is rekindled in the grainy late-night livestreams of the Eras Tour. A fisherman wakes to sing back the dead. A girl rescues dusty vinyls from the local corner shop. A disillusioned thirtysomething finds solace in piano renditions of the Beatles.

Rousing and introspective, nostalgic and exciting – from birdsong to ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ – this is the sound of Issue 003: Undersong.

Gosia Buzzanca was born in Poznań, Poland. She began publishing short stories in 2002, before moving to the UK in 2008 and earning a Creative Writing MA with distinction. In 2022, she was the recipient of the W&A Working-Class Writers’ Prize. Her debut, a memoir, There She Goes, My Beautiful World, set in between Poland and Wales, will be published by Calon in October 2025. She now lives in Barry, South Wales and is working on her first novel.