Journalist and writer Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett tells us about how motherhood has – and hasn’t – changed her writing life.

I went through to see my 3-year-old son for cuddles. It’s a good thing that I was never much of a morning writer, because having a small child would undoubtedly scupper that sort of routine. In fact, I have never had much of a writing routine at all. I have never been one of those writers who can bash out 2,000 words a day. I can be consistent and disciplined when I’m in the flow of a project, but I have to be at a creative stage with it where it feels very vivid to me. Before that happens I spend a lot of time daydreaming about it, and only putting the words down when I feel like it. As a result I am slower than I would like, but I do think the work benefits from all that time and air.

I’m not in my workspace, I’m in the living room. In front of me is a clothes horse festooned with drying childrenswear, offset by an overflowing basket of dry laundry that won’t be put away today. In my direct eyeline is my son’s play kitchen in which he has no interest, so it’s become a sort of storage unit for vinyl records and socks. There are way, way too many books everywhere, including a box of Republic of Parenthood proofs that I have been posting out to early readers. The room is a mess but it’s an improvement on yesterday, when I found a turd on the carpet – probably the cat’s but it’s hard to know. I didn’t look too closely.

Nothing! I have two books coming out in the space of six months so I fear trying to write anything new would actually push me over into madness. I told my husband I wouldn’t write another book for at least a year and I am trying, for my own sanity, not to renege on that, but in the last couple of days my mind has started percolating and I am wondering – do I return to an idea that has been simmering for many years, or do I start something new, probably set in Italy? I don’t know why Italy is drawing me so powerfully at the moment but it is. I also have the kernels of what I think is going to be a short story. In fact it’s pretty clear that I am not going to be waiting a year to start writing again.

On my Kindle, something by a writer I love that I really shouldn’t have a copy of yet, so I can’t say in case I get the person who gave it to me in trouble. I am also rereading Heating & Cooling: 52 Micro-Memoirs by Beth Ann Fennelly. It’s wonderful; I always enjoy autobiographical writing that takes a creative approach, and this is both funny, moving, and eccentric in the best way. I’d love to write something like this but something this quirky and unconventional can be a hard sell.

Tree-book wise, I have been reading Our Evenings by Alan Hollinghurst for a year now. I’m a speed reader so this is extremely slow for me. It’s nothing to do with the content of the book – he’s a phenomenal writer and this latest novel is one of his best – and more its materiality. For much of last year I shared a bed with my son so could only read on my device, in the dark. I’m happy to say he now sleeps very well on his own and I can go back to reading paper books again.

“There’s an emotional rawness and viscerality to [the weeks just after having a child] that we rarely see documented, understandably because it’s so utterly all-consuming. So much of early motherhood is constructed in retrospect as a result. I wanted to write through those wild weeks, and had already signed up to do so before he arrived, but the cosmic, brutal reality of living in a maternal body doesn’t hit you until you’ve given birth.”

The Baby on the Fire Escape by Julie Phillips is a must read for any woman who fears the impact of the ‘pram in the hall’, a bullshit, sexist phantom created by men. This book showed me how so many women artists and writers have integrated their practice into their domestic lives however they were able, and produced astonishing work as a result. It taught me not only that motherhood and creative work can be compatible, and that there is no roadmap for negotiating that, you can only work it out yourself, but also that motherhood can complicate and enrich art in ways that make it even more vital and resonant. Along with The Laugh of the Medusa, Hélène Cixous’ 1975 essay about ‘écriture féminine’, it has been fundamental to my writing practice.

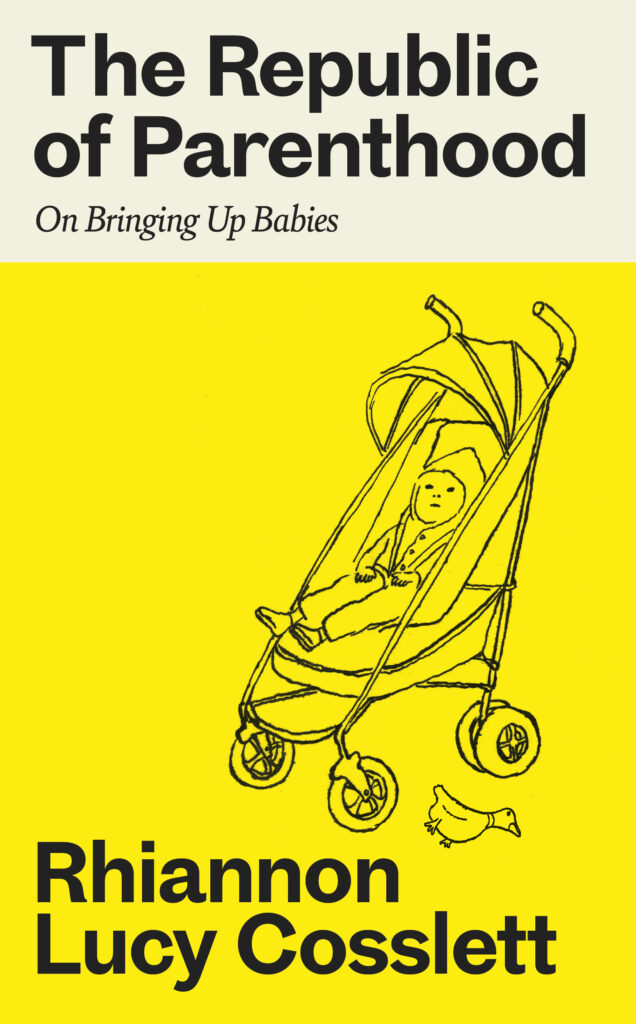

The birth of my son and the weeks following. There’s an emotional rawness and viscerality to that time that we rarely see documented, understandably because it’s so utterly all-consuming. So much of early motherhood is constructed in retrospect as a result. I wanted to write through those wild weeks, and had already signed up to do so before he arrived, but the cosmic, brutal reality of living in a maternal body doesn’t hit you until you’ve given birth. That feeling – of awe mixed with terror – I wanted to bottle that in print for everyone who has ever felt it. It also completely changed the course of my upcoming novel, Female, Nude, half of which I had written before I had him. Returning to it after becoming a mother, having sold it on a partial manuscript, felt epiphanic. It was a moment of going: ‘oh, this is why I stopped writing here. I couldn’t write this book without having lived through matrescence,’ it was too fundamental to the core of the story.

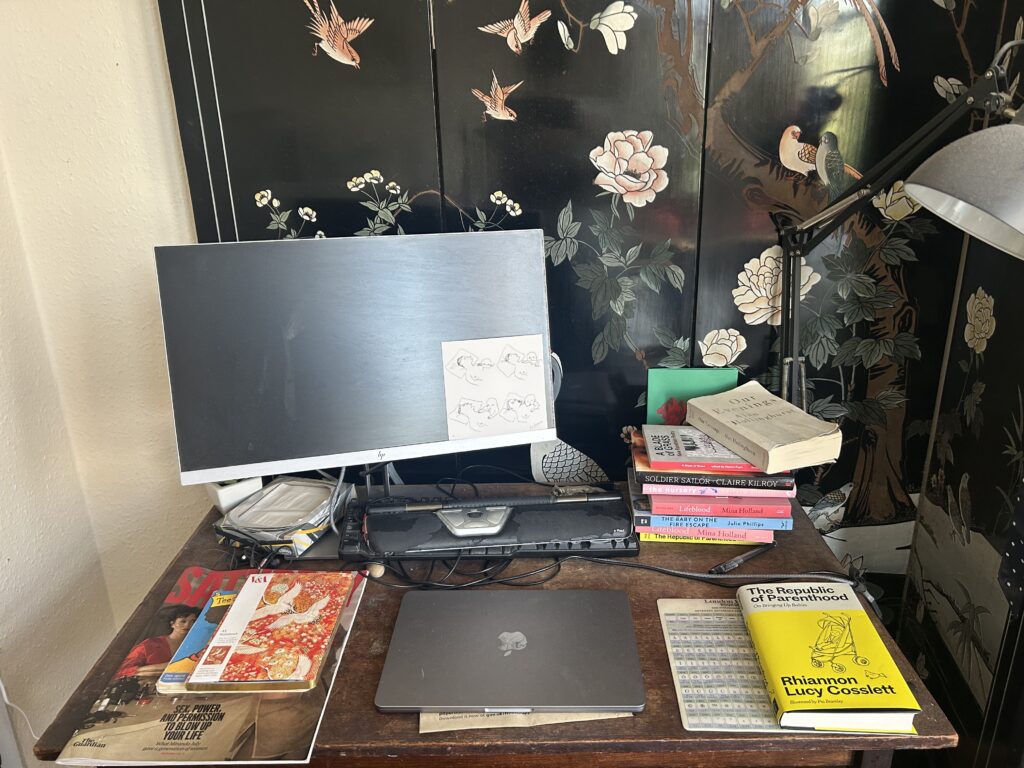

Like probably all freelance writers who find out they are pregnant, I had a horror of becoming forgotten and obsolete, so working on the basis of ‘everything is copy,’ I pitched a column about it to my editors at The Guardian. That sounds glib, because it wasn’t the only reason – I felt that our generation of parents faced a unique set of pressures that were worthy of examination, and there was a lot of bad writing about parenthood around at the time. This book is a collection of those essays alongside new material and beautiful illustrations by the artist Pia Bramley, whose work really captures that feeling in early parenthood where you are having the best and also the worst time of your life sometimes in the space of five minutes, and that wild mix of hope, love and fear. I had a very clear vision for the book from the start. I didn’t want it to be another collection of columns with the writer making a quizzical expression on the cover; I wanted it to be a beautiful object, something that can be given as a gift to new parents embarking on that journey, which will hopefully make them feel validated and less alone.

I learned the validity and importance of writing certain experiences in real time. I had already done that with The Year of the Cat, my memoir, which takes place over a year of the pandemic when I felt desperate to become a mother but worried the world was going to hell, so adopted a kitten instead, but it really crystallised with those early parenthood essays. I think I would have forgotten everything, or put more of a rose-tinted spin on it, had I tried to do it from memory. I now passionately believe in the importance of supporting mother-artists so that they can make work about their experiences at the same time as living them. To an extent real-time artmaking can be said to have been, historically at least, a very male privilege.

I love what I have come to think of as the ‘swimming and thinking’ stage. There’s something so meditative about swimming that it seems to make you dreamy and receptive in a way that’s perfect for when you are still waiting for the images of an idea to grow in your mind. But as a hack, I also love to be edited. Each book is a collaboration between a writer and an editor and I am quite proud of the fact that I am generally not precious and can take a good edit. I feel really lucky to get to work with the editors that I do.

Honestly, probably last summer when I was finishing Female, Nude and I went to stay with friends at their house in Provence. (That makes me sound grander than I am: I used to be their babysitter, when I lived in Paris on my gap year, and we have stayed in touch over the years.) It has a 19th century stone swimming pool that they call ‘le basin’. Each morning I would swim in it before breakfast, then would go up to my room to write to the sound of the crickets and the wood pigeons. The room was very simple: just a desk with a laptop, a bed, and a wardrobe. I would sit there typing away with my feet warming on the tiled floor. Then my friend’s mother, who is in her 80s, would make something delicious for lunch, served with a few mouthfuls of rosé which they get from the local vineyard co-operative and decant into bottles from those big plastic jugs people use for petrol. After that, an afternoon lie down and then more writing before another swim and a very late dinner. I don’t think I’d have finished my book were in not for this place and these friends! They were so generous and I feel very lucky for the time and space. So many writing retreats seem to last too long to be compatible with motherhood, so this was perfect.

I don’t dwell, really: once it’s out there, it’s out there. Saying that, I hadn’t looked at my first novel, The Tyranny of Lost Things, since it was published in 2018. I wondered if it might be terrible but actually, flicking through it, I was pleasantly surprised. There are things I would change, obviously, but then it would be a very different book. Had you asked me at the time I’d have probably said something very different. One critic said that I did too much telling and not enough showing. I’ve always been inspired by Italian literature, which I studied and which is often all telling, but it was still wounding. Now I’m more confident and think rules like ‘show don’t tell’ are for idiots. I loved Naoise Dolan’s recent essay on how tediously neurotypical ‘show don’t tell’ is (also modernism, hello?). Imagine if I had lacked confidence and listened! If anything, my next novel leans even more into telling than the one before.

It’s out of print now because the wonderful press that published it went under, as sadly so many indie presses do, but I’m very proud of it. It’s essentially a gothic novel about trauma set in an urban commune. A housing crisis novel before that was a thing! And it’s a love letter to London in the summer. I think I captured the hallucinatory, almost feral feel of the city in a heatwave rather well.

I think projects are like children: you love them all for and not despite their different qualities. But there’s an article that I wrote for The Guardian about the experience of growing up with my autistic brother that I couldn’t be more proud of. Loving him has defined my life in so many ways, not least in the importance of laughter through tears, but perhaps most fundamentally in my belief that art is what saves us.

Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett is a journalist and writer. She is the co-author of The Vagenda, and the author of the novel The Tyranny of Lost Things, and the critically acclaimed memoir, The Year of the Cat, about deciding whether or not to have a baby. She is a columnist for the Guardian and Vogue, and has written for Elle, Stylist, the New Statesman, the Independent and Time.

Image © Paul Tschornow at Photo Heads.