Double exposure is a technique in analogue photography where the film is exposed multiple times, usually by manually winding back the unspooled film so that the eye of the camera exposes the same piece of gelatine-emulsified cellulose triacetate to light multiple times. A second image is captured over the first, both showing ghostly in the final photo. They can be taken in immediate succession, capturing movement within the same frame, or combining different angles on the same location. Or they can be two disparate images, the camera forgotten for weeks until you no longer remember the last image you took, so that the new, second exposure has only an accidental relationship to the original, leaving the viewer to plot significance or meaning onto the result.

It is a clumsy process, this manual respooling. No counter or tape to show you how far you’ve gone – too little, too much? Will the frames align, or will the images leave overlapping edges?

There is an image, in Sweet Melancholy, where these edges do not align. The book contains around forty photographs from the work of Elin Gruffydd, along with a couple of archive images of Brenda Chamberlain (1912–1971), the muse behind Elin’s study in photography of two islands: Ynys Enlli in Wales, and Hydra in Greece. The book is in three languages: Welsh, English and Greek, with Greek translations by Claire Papamichael. Elin’s pictures are taken on 35mm film, in both colour and black and white, creating a collection of grained, vaguely timeless photos.

Brenda, a writer and artist, spent fifteen years living on Enlli and then six years on Hydra. Over half a century later, Elin spent two springs and summers living and working on Enlli, in the shadow of Brenda’s presence, before going on to study the Classics, following Brenda to Hydra, and developing an interest in the women of the Greek myths. It is these multiple exposures that she puts forwards in Sweet Melancholy, interposing quotes from Brenda’s work – from A Rope of Vines: Journal from a Greek Island (1965) and Tide Race (1962) – with her own photographs of these two islands: impressions upon impressions.

The photograph I am thinking of, with its overlapping edges, comes towards the end of the book, and is a black and white photo. The camera looks across a large rock pool or a shoreline, towards a rocky amphitheatre, where two or perhaps four figures move carefully across the large rocks. They seem impossibly small. Two lines cut across the image. The first is a clean line across the bottom, where the bottom of one exposure cuts across the other. The second is a meandering ‘v’ shape that cuts across the top of the picture. I zoom in and peer at my dirty computer screen, trying to make out what it is, who belongs to which exposure. Am I looking at sky or rock or something else entirely? I look again at the figures. The four could be the same two, posing twice. In one they are holding on to each other as if to steady themselves. In the other pose they are apart, the figure in a dress balancing impossibly as she steps across two large boulders. Their reflections appear in the water below, four figures becoming six. The quote that accompanies the image on the opposite page could be from either of Brenda’s books:

‘Now, on this island, I have found a way of life again.’

The connection between the two islands portrayed in this book is a loose one – Hydra is home to over 2,000 people, and has an area of 20 square miles, while Enlli is home to around eleven residents, and is only 0.7 square miles in area. In some of these photos it is clear which island is which, but her images seek to assimilate rather than contrast, and in many images it is difficult to tell, as the differing landscapes blend impossibly. But it is not simply a case of blurring the edges: Elin Gruffydd also actively builds a visual relationship between the two islands, through shared themes and textures. Blues, in the waters and the skies, chipping blue paintwork, pale blue walls dappled in shade. A close-up image of a time-worn sculpture in white stone that conjures the foaming waters of Enlli in the unexpected coarseness of its texture. Olive-green and sun-scorched hillsides, amber sunsets. Birds in flight, a battered shoreline. Elin’s images create an ahistoric dreamscape, sparse visual clues pinning the images to a particular place or time – a blurred glimpse of a JCB in the bottom of one photo, a New Balance sneaker out of focus in another. She seems to almost try to bridge the gap between herself and Brenda, by compressing time and creating a space that they could both occupy. It is a dream book: these are pages to float through.

—

One Woman Walks Europe is a book that brings us back onto solid ground, in a literal sense. It is the story of a woman walking across the continent of Europe, from Kiev to Finisterre, to Llanidloes. It is a journey that spans three years and 5,500 miles. In some ways it is the simplest story in the world: I went for a walk, and this is what I saw. There were flat bits and there were steep bits, sometimes it was warm, sometimes it was cold. Sometimes there was enough to eat, sometimes there was not. It is the story of a woman moving across space, one footstep at a time.

If there are multiple exposures at work here, it is in the knowledge that the reader has of what is about to happen to the landscape that Ursula Martin has just traversed. She arrives in Ukraine in 2018, and Russia has annexed the Crimean Peninsula since 2014. It is not until 2022, when Ursula is back in Wales, that the full-scale invasion of Ukraine by Russia takes place. The Ukraine that Ursula has crossed likely no longer exists. Over the picture described by Ursula we see the news images of the falling bombs and the tumbling down of the global geopolitics.

But for now, we are walking. We are crossing fields and forests, impossibly slowly, and the structures of narrative strain against this slowness. Nothing is happening, and the book seems to be formed of fragmented descriptions, impressions and reflections that buoy us along: ‘The journey was sometimes nothing more than a series of strange interludes that I flowed between, dipping into other people’s worlds like a bird on the wing.’

As I read, I have been trying to reach in my mind for what this book reminds me of – and finally it comes to me. It is the often overlooked second part of The Hobbit’s title: ‘There And Back Again’ – the playful summary of an epic quest that, at its core, is a journey there and back, but which also features dragons and self-discovery and other perilous interludes.

And perhaps there is something of the hobbit in Ursula – she is quick to impress upon us that she is not a glamorous athlete, but a plodder by nature. She complains constantly about her aching muscles, is always thinking of food, and is uncomfortable with the traveller as ‘hero’.

Unlike in The Hobbit, however, there is no dragon for Ursula to defeat. This is where she is more Le Guin than Tolkien, and I find myself thinking of Ursula Le Guin’s ‘Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction’. In this essay, Le Guin questions our fascination with the pointy-stick type of story, where a hero sets out with some kind of pointy stick and probably kills something. Le Guin is drawn to a different kind of story, one not rooted in the archetype of the hunter but that of the gatherer: the one who goes out with a container and fills it with nuts and fruits and other interesting bits. This is perhaps a better way to understand Ursula Martin’s book – as a carrier bag of stories that she fills as she goes.

Ursula Martin is plodding along through a vaguely timeless world, where the seasons turn but the precise moment is not immediately clear, or relevant. To be in constant motion is to be outside the normal flow of time, even though its presence hovers constantly, in the form of an enforced break in the journey, when Ursula must pick home to Wales for a hospital visit to monitor her cancer. This is not a dragon that she is battling, but a limitation and challenge that has shaped the trajectory of her life. However, Ursula is not without agency in relation to this force, and this book is partly about how she has chosen to wield that agency.

And then suddenly history comes crashing in, unavoidable and with a brute force, in the form of the Covid-19 pandemic. The journey is halted, again and again. The carrier bag is being jostled and bumped, but still our traveller persists, leaning on the support of others, until at last she makes it to Finisterre, to Portsmouth, to the hills of Radnorshire, and over the last hill to Llanidloes, finally back again.

Both Elin Gruffydd and Ursula Martin, in vastly different ways, seem to explore the idea of time and space and how they turn up when we tell a story; Elin by compressing and Ursula by opening them up.

—

On the cover of Global Politics of Welsh Patagonia is a photograph of a white man surrounded by six indigenous men, taken in 1867. It’s a familiar, often-displayed picture for anyone acquainted with the history of Welsh Patagonia. However, usually when this picture is shown, it is only the white man, Lewis Jones, who is identified. In Lucy Taylor’s book, we are given the names of the other six – Kilcham, Yelulk, Wisel, Cacique Francisco, Kitchskum and Waisho.

In a recent article in O’r Pedwar Gwynt’s spring 2025 edition, Simon Brooks questions the validity of recent criticism of the Welsh colony in Patagonia, suggesting that Y Wladfa is subject to unfair scrutiny that is not given to other settler colonies such as the United States. It is a claim that seems to ignore the colossal body of work that examines the USA’s roots in genocidal violence against indigenous populations and the slave economy, and discourses surrounding reparations, indigenous land justice movements, Black Lives Matter and other movements seeking to address the foundational violence of the USA. In contrast, discourse surrounding Y Wladfa in Wales has until very recently barely engaged with the existence of the Tehuelche, Pampas and Mapuche peoples, their complex history with the Welsh settlers, and more importantly their continued presence, political disenfranchisement and erasure in the present moment.

This is the correction that Lucy Taylor seeks to redress with this book. She sets out with a nuanced approach to adjust the lens on Patagonia, opening her book not with the familiar story of the Mimosa’s voyage, or the friendship between the Welsh and ‘the children of the desert’, but with the voice of a Mapuche man named Katrülaf, who was interviewed in autumn 1902 by a German anthropologist about his life and his experience of the Conquest of the Desert. This was the military campaign led by the Argentinian state between 1870 and 1884 to clear the ‘desert’ of indigenous peoples, to facilitate its occupation by white settlers (including the Welsh in Chubut). It led to the deaths of 1,000 people, and the displacement of 15,000 more, and many, including Katrülaf, were forced into slave labour.

Travelling to Where The Welsh Are (the Mapuche name for the area of Chubut occupied by the Welsh), Katrülaf is captured by the Argentinian military along with other Mapuche men, then marched between military posts where they are corralled like animals, before being sent over 800 miles away to Buenos Aires where he is forced to serve in the Argentinian Army for six years.

This is the first time that the first-hand account of the experience of any indigenous person of Patagonia has been included within a history of the Welsh in Patagonia, even if, as Lucy emphasises, this account is also brought to us through a series of slippages, via transcribers and translators.

However, her account is not of a simple binary between coloniser and colonised. She argues that the Welsh represented both simultaneously – a not uncontested claim, but one that she bolsters with the argument that we should not appropriate the discursive language that has been built around the postcolonial movements of the global majority, but rather develop concepts that are relevant and appropriate to a country whose colonisation began much earlier, and who formed a complex relationship of complicity and resistance with the colonising nation. One such concept that she puts forward is that of ‘barbarisation’: the idea of a hierarchy where the centre conceives itself as ‘civilised’, and constructs the other’s lifeways, culture and language as less civilised, and therefore lower on the hierarchy. And so Lucy argues that:

A shift to the broader category of barbarisation creates an intellectual space that both Indigenous Patagonians and the Welsh can inhabit. This is not to say that their experiences are equivalent: clearly the stakes for the Welsh were and are much lower than that of Katrülaf and his descendants, and their position on the grim hierarchy of oppression is much more comfortable. Yet this does not shield them and their language from being the object of derision and prejudice.

This holding of two seemingly oppositional facts simultaneously feels like a kind of double exposure. Two contrasting pictures superimposed, creating a tangled image that is not always easy to understand, or identify with. Imagine that first photo, of Lewis, Kilcham, Yelulk, Wisel, Cacique Francisco, Kitchskum and Waisho, ruptured and bisected and intersected by the lines of subsequent exposures, by other pictures.

There is still much work to be done on our understanding of the story of Y Wladfa, to de-mythologise and unpick what was in some ways propaganda necessary to bolster support and ensure the survival of the Welsh in Patagonia. In Global Politics of Welsh Patagonia, Lucy Taylor provides guiding principles and shows us possible pathways – and one path is two, sitting with these multiple exposures. It requires understanding the complex stories of the real women and men who were involved (Tehuelche, Pampas and Mapuche, and Welsh), and an appraisal of how the Wladfa mythomoteur is constructed and consumed here in Wales.

Saunders Lewis once described the story of Y Wladfa, as written by R. Bryn Williams, as a national epic, its classical subject comparable to Virgil’s Aeneid – of a small band setting off to search for a new Troy. What we need is less Greek epic and more of what Lucy offers: accounts of the individuals caught in the currents of global politics, and how those currents ripped through their lives, told with nuance and dignity.

I think again of the ghostly figures in Elin’s photo, of the figure stepping, of the unaligned edges, and I think of Ursula’s carrier bag of walking tales. There is an inherent messiness that appeals in all these works, in the same way that it’s the random potential of mess in a double exposure that makes this kind of photo so compelling. Even in Lucy’s work, we are asked to accept a messy-ing of the narrative that is not an obscuring but a clarifying force.

Click – whirr – Click.

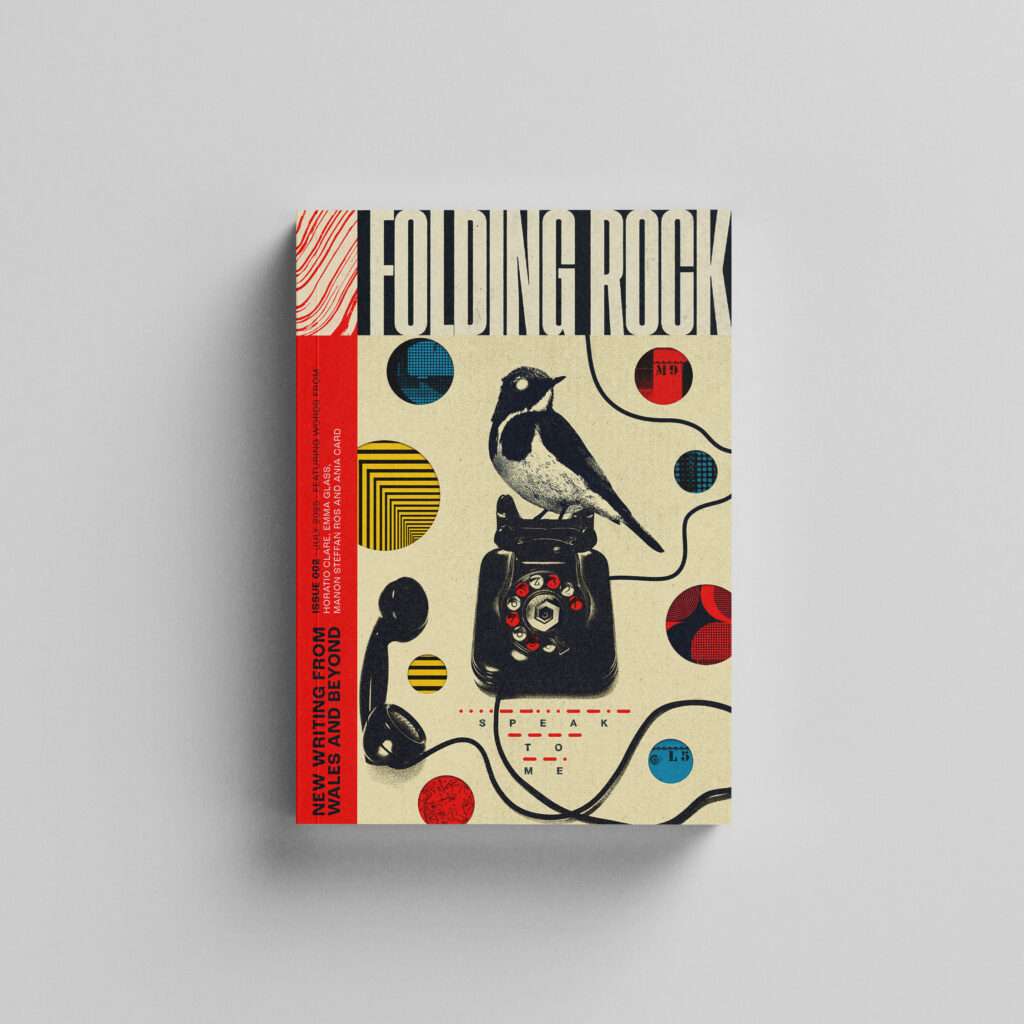

Featuring new work from writers including Horatio Clare, Emma Glass, Manon Steffan Ros and Ania Card.

The multitude of languages we use to communicate, be they spoken or non-verbal, are arguably the most integral – and human – elements of our social existence. A painting can change a life. A telephone call can save one. A smile can, at times, reveal more than the most epic of soliloquies, while at others, a whisper can be deafening.

Grug Muse is a poet and writer from Dyffryn Nantlle, who is now living in Bro Ddyfi. She published the poetry collection merch y llyn in 2021 (Cyhoeddiadau’r Stamp), and is one of the co-editors of Welsh (Plural) (Repeater, 2022). She is co-editor of the poetry journal Ffosfforws.