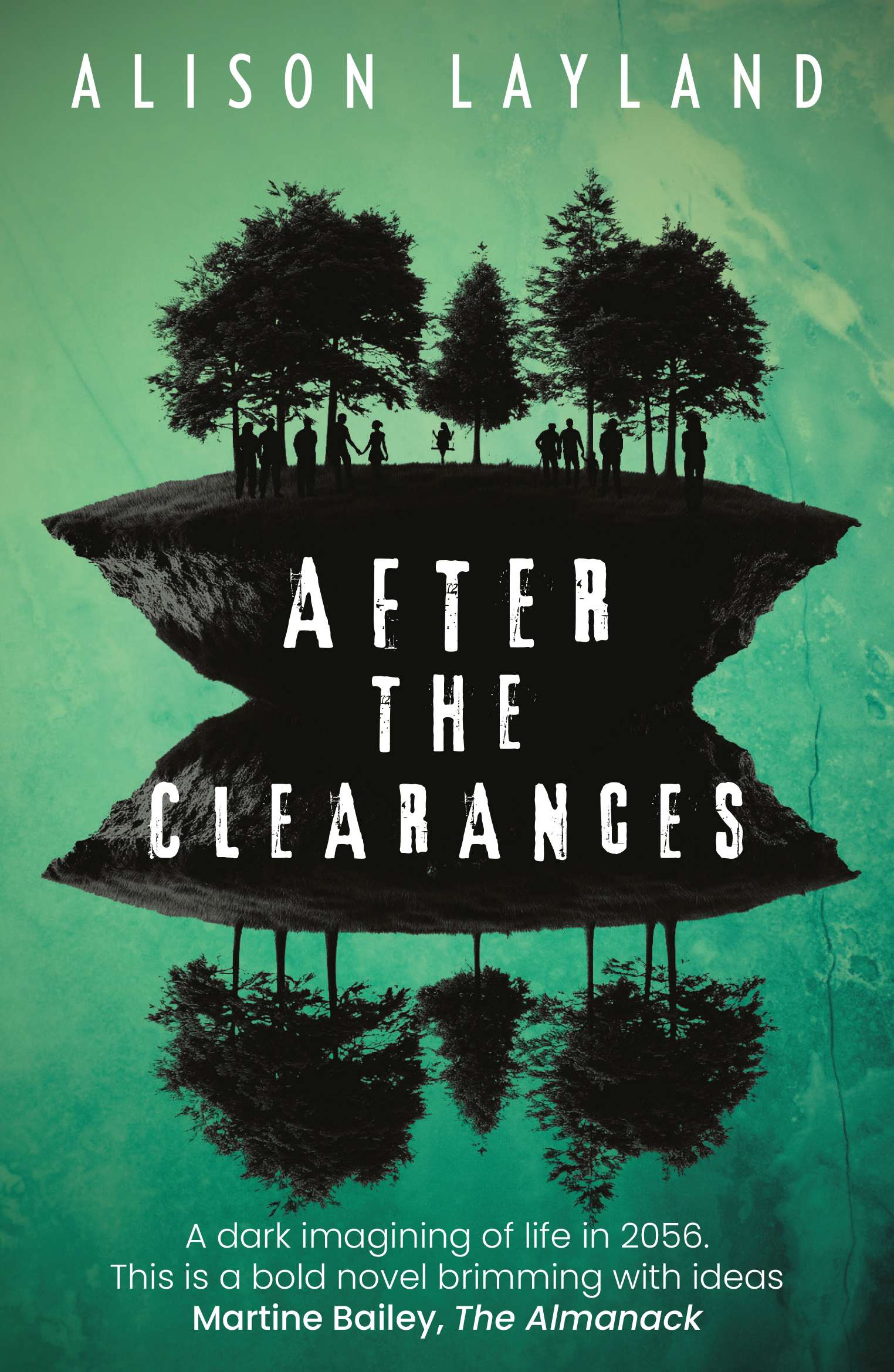

Rosy Adams considers the approach of ‘thrutopian’ fiction, with Alison Layland’s thought-provoking new cli-fi novel After the Clearances.

The best speculative fiction grows out of a comprehensive understanding of our world as it is now, and it’s clear that Alison Layland has just that. She weaves a compelling narrative in which ideas of the fragility of language and identity are inextricably bound up with the changing climate. Her characters are shaped by the places they call home, and in turn they are responsible for shaping what those places will become.

‘Ry’n ni’n yma o hyd

Er gwaetha pawb a phopeth

We’re still here

Despite everyone and everything’

This quotation from Dafydd Iwan’s song ‘Yma o Hyd’ is the last of three epigraphs at the beginning of After the Clearances. It’s particularly apt here as the novel opens in 2056, some years after the titular clearances; a government resettlement programme which has moved swathes of the rural Welsh population to urban areas. But despite this, there are persistent remnants making do in abandoned and overlooked spaces.

The narrative is shared between four characters: Glesni, born into the Seeder community on the fictional island of Ynys Hudol (inspired by Ynys Enlli), who longs to visit the Mainland on one of the infrequent foraging trips; Sandy, a stranger from Manchester, the centre of government since London’s abandonment due to rising sea levels, who washes up at the island on a broken-down boat; Bela, a semi-feral young woman haunting a run-down farmhouse which is slowly disappearing into the wilderness; and Winter, a man on the run who takes refuge with her.

Excerpts from ‘Seeds of Change’, the Seeders’ manifesto, act to flesh out the history of the community of Ynys Hudol. Fragments of news articles give a broader picture of this near future Wales. The narrative is fraught with tension between local and global, from politics to language to weather.

I’m usually a fast reader, but I found myself needing to take it slow with this book. It’s partly the way the narrative is passed between the characters, particularly the switch between Bela’s unfiltered stream of consciousness and the more traditional close third person of the others, but it’s also the change of perspective – the way the world changes in accordance with the characters’ beliefs and values. In addition there’s a lot of information to take in (to be expected with the world-building aspect of speculative fiction) and there’s also the need to include aspects of Welsh history which are essential to the plot but aren’t well known outside Wales. It’s not easy to get all that in and still have a story that keeps you engaged, but Layland does it with panache. Even the character of Sandy, who I didn’t find particularly likeable, managed to evoke my sympathy by the end.

The effects of climate change are a constant backdrop to the story, but Layland manages to avoid the trap of preaching at us. Unpredictable weather and rising seas are referenced as they directly affect characters’ lives. Fierce storms force them to take shelter and wait it out, either in the communal roundhouse on the island or on the mainland wherever they can:

‘Four whole days holed up in an abandoned house at the edge of a deserted village. The sea, which would once have been on the far side of the road, was now lapping up the garden as if the house were venturing to dabble its toes in the water.’

History is inescapable, from the echo of the Highland clearances at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, or ‘Cofiwch Dryweryn, in its distinctive red cloud’ recalling the drowning of Capel Celyn to provide water for the city of Liverpool in the 1960s.

Layland highlights the impact of sweeping directives from a distant government with no empathy or understanding of the land, the people, even the language. The difference between the language of government and of the affected population is clear in ‘resettlement’ as opposed to ‘clearances’.

There is a pervasive sense of linguistic instability in the text, the fluidity of meaning between English and Welsh most obvious in the English name for Ynys Hudol, Aniseed Island; a sounds-like as opposed to a translation, which influences the bi-lingual community to call themselves The Seeders. In the opening diary entry Glesni tells us in an aside:

‘[…] my taid (…pronounced “tide” Sandy told me early on that she imagined a name like that for an old man with the unstoppable ebb and flow of life, or some indication of dependability, like the ever-present sea. She looked a bit disappointed when I told her it only means Grandpa. I must admit her view of it makes beautiful sense.)’

The cover lists it as Climate Fiction, a relatively new genre which is often speculative but not always. Abi Daré’s novel And So I Roar, winner of the inaugural Climate Fiction Prize, for example, is set in 2014 and is very much concerned with the world we live in now.

I’ve avoided media concerning climate change in the past, not because I’m trying to pretend it isn’t happening, but as a kind of self-protection. It’s not that I don’t care, but that I care too much, and I feel powerless in the face of it all. The Climate Fiction Prize website states that ‘[m]any of us already see tackling climate as important; but we don’t always know how we should respond. Fiction can help us imagine what change can look like.’

After the Clearances does exactly that. It’s a thoughtful exploration of what our future could look like. Neither utopian ideal nor dystopian nightmare; instead Layland gives us a thrutopian vision, one that acknowledges the messy spectrum of our humanity and still gives us a glimpse of hope.

Rosy Adams is a poet and fiction writer from Powys. She was part of Literature Wales’ second cohort of Representing Wales writer development programme in 2022/23, which led her to set up a Community Interest Company to organise and fund on-going support for under-represented writers in Wales. She edited and contributed to (Un)common: Anthology of new Welsh Writing (Lucent Dreaming, 2024). Her writing has been published in The Lampeter Review, Lucent Dreaming Magazine, These Pages Sing, Gwyllion and Poetry Wales among others. She is in the final stages of a collection of contemporary short stories influenced by myth and fairytale, and she has a novel in development.